Where we left off

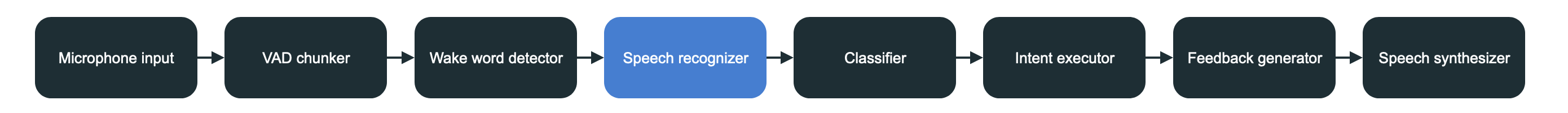

In part 3 of the mini-series, we implemented a fast wake word detector to make sure Jarvis only responds to audio meant for it. But now it actually needs to convert the audio into a usable form for other stages of the processing pipeline: text.

Goal of this post

Our aim now is to take the audio data and convert it into text, commonly known in the programming world as Speech to Text (STT). To do this, we’re going to utilize one of the better and more popular libraries out there - OpenAI’s Whisper.

Whisper

I probably don’t need to say much about OpenAI. Their name is ubiquitous and almost everyone is well familiar with their flagship product, ChatGPT. However, they’ve developed and released a lot of other very useful libraries. I’m definitely all for coding my own STT ML model, but I could spend ages doing just that without ever finishing, and I also suspect it might not work as well as the one from one of the most famous AI companies out there. So I’ll just stick with Whisper for now.

The original Whisper library is written in Python, which we could use via bindings to Rust, but there’s a very peculiar person out there by the name of Georgi Gerganov who maintains a port of Whisper written in pure C++. It’s very performant without any dependencies, which makes it very portable and suitable for our needs. And there are also Rust bindings written for it.

This is the library we’re going to use. Looking at the Rust bindings repo, there’s also a short example of how to go about using it. Let’s get down to it then!

AI models

Virtually all broadly used machine learning tools that operate today have one common denominator: they’re all based on the Transformer architecture. I could spend ages talking about transformers, but there’s one important thing to point out: the underlying architecture of every AI tool out there is relatively similar.

The way ML works is by figuring out how important a piece of an input sequence is and how it correlates to the output. In practice, the result of doing ML training is usually a file that stores all of the “importances” or as they’re actually known - weights. Those weight values combined with a particular configuration of the different math-performing blocks are called a model. This means that using a different set of weights (the definition of what is important) with the same network configuration can produce entirely different results. This is so useful that there are entire sites for sharing weights and other configurations.

It is precisely because of that that we could use Jarvis in a language different than English. If we use a different model than the one I’m using, it’ll just recognize a different language. We would have to make some other modifications though - you’ll see later on that we use English for figuring out what command needs to be triggered. But we could easily modify that too.

I’ve included some models in the models folder. But many more can be downloaded and used.

Speech recognizer

Instead of following the usual functional approach of having everything in the main function of each processing step and having supporting functions in the same file, I’ve decided to take a more encapsulated approach here. We’ll create a speech_recognizer.rs in core that will contain most of the speech recognition logic and then plug that into the processing pipeline. That way it’s reusable and neatly self-contained.

Let’s flesh out the basic structure of our recognizer:

pub struct SpeechRecognizer {

context: WhisperContext // Instance variable we want for recognition

}

impl SpeechRecognizer {

pub fn new(model_path: &str) -> Self {

SpeechRecognizer { context }

}

pub fn default_model_path() -> String {

}

/// Make sure audio is in 1 channel 16k sampling

pub fn recognize(&self, audio: &[f32]) -> Result<String, WhisperError> {

}

}

Our new function will load the weights, create the model, and make sure we can run it. default_model_path is just a shorthand so that we don’t have to construct a file path on the fly but can fall back to this one. Finally, the heavy lifting function is recognize, which will actually run the AI model.

We’ll be using the small model because it works sufficiently well and doesn’t take up too much system memory.

pub fn default_model_path() -> String {

PathBuf::from(env!("CARGO_MANIFEST_DIR"))

.join("models")

.join("ggml-model-whisper-small.en.bin")

.to_str()

.expect("No speech recognizer model found at the default path.")

.to_owned()

}

We have an expect here, but I’m okay with the program crashing and burning if a model path can’t be constructed since there’s no way to recognize speech anyway. And there really is no excuse for not providing a model.

Context

Next up is creating the context and actually constructing SpeechRecognizer.

// I was bothered immensely by logs from whisper

// so I added an empty replacement callback for logging messages

extern "C" fn silent_log_callback(

_level: u32,

_message: *const i8,

_user_data: *mut std::ffi::c_void

) {

// noop

}

// Creates a new SpeechRecognizer

pub fn new(model_path: &str) -> Self {

// We could specify different parameters for recognition

// but the default ones work well for our use case

// I encourage you to play around with this as I

// had a lot of fun doing so

let params = WhisperContextParameters::default();

let context = WhisperContext::new_with_params(model_path, params)

// I'm okay with crashing here because we need to

// be able to create a context

.expect("Unable to create SpeechRecognizer WhisperContext. Did you specify the correct path?");

// Plug in the actual log callback into the C based lib

// meaning this is `unsafe` code

unsafe {

whisper_rs::set_log_callback(Some(silent_log_callback), std::ptr::null_mut());

}

// return Self

SpeechRecognizer {

context

}

}

Most everything is already explained in the comments of the above block of code, so we’ll move on to the actual juicy part of this struct - the recognize method:

/// Make sure audio is in 1 channel 16k sampling

pub fn recognize(&self, audio: &[f32]) -> Result<String, WhisperError> {

// Create a recognition state

let mut state = self.context

.create_state()?;

// We define some parameters about the input clip and

// what kind of processing we'd like. A greedy sampling strategy

// means the model will try to fit the audio to some text

// regardless if it doesn't fit well

let mut params = FullParams::new(SamplingStrategy::Greedy { best_of: 1 });

params.set_print_progress(false); // No logging

params.set_single_segment(true); // Our audio is in a single clip

// If we uttered a short piece of audio, we need to pad it to be

// at least 1s long otherwise whisper will not trigger

// recognition

let dif = (AUDIO_SAMPLE_RATE as i64) - (audio.len() as i64);

if dif > 0 {

let mut audio = audio.to_vec();

audio.extend_from_slice(&vec![0.0; 16000]); // Add 1s of blank audio

state.full(params, &audio)?; // Run the model

} else {

state.full(params, audio)?; // Run the model

}

// Construct the string from the segments, see the repo

// readme for usage details

let num_segments = state.full_n_segments()?;

let mut text = String::new();

for i in 0..num_segments {

match state.full_get_segment_text(i) {

Ok(str) => text.push_str(&str),

Err(_) => continue

}

}

Ok(text.trim().to_string())

}

In part II, we implemented a resample_audio function that converted to a 16k sampling rate. This is the reason why. Whisper works with single channel, 16k samples, f32 audio data.

Integrating the Speech Recognizer

Now that we have our SpeechRecognizer ready, let’s integrate it into our processing pipeline. We’ll create a new file recognizer.rs in the processing directory:

use std::sync::mpsc::{Receiver, Sender};

use crate::core::speech_recognizer::SpeechRecognizer;

pub fn main(chunker_rx: Receiver<Vec<f32>>, recognizer_tx: Sender<String>) {

// Create our recognizer

let recognizer = SpeechRecognizer::new(&SpeechRecognizer::default_model_path());

// Same as in other cases, if the channel breaks

// we terminate the loop and exit the recognizer main

while let Ok(audio) = chunker_rx.recv() {

// Invoke recognition. If this fails we continue

// as if nothing happened and wait for the next piece

// of audio. This isn't great as we could respond with

// some feedback but it never actually happened in testing

let text = match recognizer.recognize(&audio) {

Ok(text) => text,

Err(_) => continue

};

// Filter out a few well known phrases

// to make sure we have useful speech.

if is_noise(&text) {

continue;

}

println!("Recognized '{}'", text);

// Send the text further down the pipeline

if recognizer_tx.send(text).is_err() {

break;

}

}

}

// Check if recognized audio is useless.

fn is_noise(text: &str) -> bool {

// All of the noise and non speech has the format [SOMETHING] so it's easier to filter out by checking for the [] symbols.

// An old implementation I had was this:

// let noise = ["[INAUDIBLE]", "[BLANK_AUDIO]", "[MUSIC PLAYING]", "[TAKE VO]", "[SOUND]", "[CLICK]"];

// noise.contains(&text)

text.starts_with('[') && text.ends_with(']')

}

recognizer::main will receive audio chunks from the previous stage, run the speech recognition on them, print the recognized text and send it further down the processing pipeline. Only thing remaining is integrating it in our main.rs. Let’s do this next.

let (recognizer_tx, recognizer_rx) = channel::<String>();

thread_pool.spawn(async move {

processing::recognizer::main(detector_rx, recognizer_tx);

println!("Speech recognizer shutting down");

});

Not much we haven’t seen before. A new channel for recognizer and plugging in the wake word detector rx and recognizer tx.

Wrapping up

We’ve now added a crucial piece to our pipeline - converting raw audio into text using AI-based speech recognition. This sets us up perfectly for the next stages where we’ll interpret the text and take actions based on it. In the next post, we’ll dive into classifying the recognized text into commands Jarvis can act upon. Stay tuned!