Where we left off

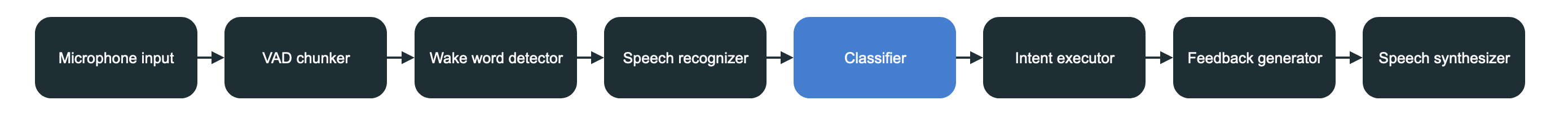

Part IV finally touched the AI aspect of Jarvis and converted speech from audio to text. We now have the input audio part of the pipeline done. It’s time to decide what to do.

This is going to be a long one so get your beverages and snacks ready.

Goal of this post

What we want to achieve in this post is to take the recognized text and parse it so that we can determine what the user wants us to do. What we’ll be doing here is implementing the brain of Jarvis and as such there’s a lot of possibilities of how to go about it.

We’ll keep things simple but demonstrate how to classify between various kinds of commands and how this could be expanded further. For instance this is the step where we could plug in to ChatGPT’s API here which would result in a lot more powerful assistant. But that is the opposite of what I wanted to do - I wanted to figure out the problem for myself and see how one could implement an command recongition system.

What is classification anyway?

I’ve used the word classify as the noun of what happens when determining what command the user meant. By definition the word means a category into which something is put. And that already hints at what we’ll be trying to achieve. We need to define the various commands and other functionalities Jarvis can run, and then determine into which of these categories the incoming text belongs to. So let’s get started with defining our commands.

Commands

At the core Jarvis’ purpose is to run commands such as increasing temperature, turning on lights, closing window blinds, … We’ll also add the possibility of answering questions. But initially we’ll focus on commands. So we need to define what a command is and what it consists of.

Command config

To do that we’ll create a command_map.yaml file that will contain our commands. I’ve decided on a yaml format as it’s easy to read for a person and relatively easy to parse. I’ll put the yaml map into a folder called config. Let’s take a look at an example of the structure:

commands: # root node

- "living room": # location

- switch: # action

- light # subject

- teapot # subject

- gradient: # action

- windowblinds # subject

- temperature # subject

- "dining room": # location

- switch:

- light

- hallway:

- switch:

- light

- gradient:

- temperature

- windowblinds

- bathroom:

- switch:

- light

- ventilator

The root starts with commands so that we can add other configuration options to it in the future. The content of commands is an array of locations. We group commands in our house room by room, and these are the locations we’ll be able to refer to when invoking Jarvis. One layer deeper there’s two actions defined. Currently supported are switch which indicates something can be turned on or off. Second is gradient which isn’t named great but means that something can be raised / lowered or increased / decreased. And inside actions there’s subjects on which actions can be performed upon.

This structure can be read as “In <location> we can <action> the <subject>“. For example: “In hallway we can switch the light”. This is just an example and it isn’t meant to be grammatically correct. But it’s structured to the point where it’s easy to understand and parse.

Enter commander

We need something to parse and hold our commands in Rust. But before we can start parsing and storing we need to define the model structures that reflect our command structure. These structs (called models) will go into the model folder.

Command structs

The main struct that we’re after is a Command that contains all of the relevant bits we need to actually perform something.

// model/command.rs

// You can look up what derive does

// in a nutshell it autoimplements these traits for us

#[derive(Debug, PartialEq, Eq)]

pub struct Command {

pub location: String,

pub action: CommandAction,

pub subject: CommandSubject

}

Location is pretty self explanatory but let’s add the action and subject next.

// model/command_action.rs

#[derive(Debug, PartialEq, Eq, Clone, Copy)]

pub enum CommandSwitchValue {

On, Off

}

#[derive(Debug, PartialEq, Eq, Clone, Copy)]

pub enum CommandGradientValue {

Min, Max, Less, More

}

#[derive(Debug, PartialEq, Eq, Clone, Copy)]

pub enum CommandAction {

Switch(CommandSwitchValue),

Gradient(CommandGradientValue)

}

So an action can either be a switch or a gradient as in the yaml. But it needs some extra data. A switch needs to know if it’s supposed to be on or off. We’ve got the CommandSwitchValue for that. And a gradient can either be Min, Max, Less, More. That way we can say to close the window blinds all the way or just lower them. Note that we could also add a value for Less and More so that we could say Raise the temperature by 5 degrees. But that’s beyond the scope for now.

And finally we want to define the subject:

// model/command_subject.rs

#[derive(Debug, PartialEq, Eq, Clone)]

pub enum CommandSubject {

Light, Teapot, WindowBlinds, Temperature, Ventilator

}

We could have gone with a String approach for the subject instead of parsing it into a model file which be a bit simpler but would add some complexity down the line. It is slightly annoying that for every subject we want to support we need to add an enum case but we only have to do it once so I can live with that.

These are the models taken care of. There is some missing functionality on them still but we’ll add it as we go.

Lastly there’s the CommandMap which contains the whole command_map.yaml document. There’s not much to it now but it could be extended in the future which gives us flexiblity.

#[derive(Debug)]

pub struct CommandMap {

pub commands: Vec<Command>

}

Commander

To get the commands from the config file and into a usable format we need to parse them. But in addition to that it’d also be nice to have the option of checking if a particular command is supported and so on. We’ll create the boldly named Commander for that in core/commander.rs.

use std::{fs::File, io::{BufRead, BufReader}, path::PathBuf};

use anyhow::{Ok, Result};

use crate::model::{command::Command, command_action::CommandAction, command_map::CommandMap, command_subject::CommandSubject};

pub struct Commander {

// The full array of commants

pub commands: Vec<Command>,

// A shortcut we'll see later on

pub locations: Vec<String>

}

impl Commander {

pub fn new() -> Self {

// Create the path to the map

let file = PathBuf::from(env!("CARGO_MANIFEST_DIR"))

.join("config")

.join("command_map.yaml")

.to_str()

.expect("Could not construct the command_map.yaml path")

.to_owned();

// Parse it

let (map, locations) = parse_command_map(file)

.expect("Invalid command_map.yaml structure");

Commander {

commands: map.commands,

locations

}

}

// Check if a particular command is supported

// it's a array.contains(item) check with a slight twist

pub fn supports_command(&self, command: &Command) -> bool {

for supported_command in &self.commands {

if

supported_command.location == command.location &&

supported_command.subject == command.subject &&

supported_command.action.is_same_action(&command.action) // Because of action enum values we need to have a special check

{

return true;

}

}

false

}

}

// A very crude parser for the command_map.yaml

// I tried using serde_yaml but it was more pain than

// benefit. This isn't great but gets the job done and

// is not the point of this project. You're welcome to

// parse this more efficiently and I'll happily

// update it here :)

fn parse_command_map(file_path: String) -> Result<(CommandMap, Vec<String>)> {

// Open the file to read line by line

let file = File::open(file_path)?;

let reader = BufReader::new(file);

// End result storage

let mut locations = Vec::new();

let mut commands = Vec::new();

let mut is_parsing_commands = false;

// Temp storage for constructing a Command

let mut current_location: Option<String> = None;

let mut current_action: Option<CommandAction> = None;

// For each line

for line in reader.lines().flatten() {

// We get the line indentation (how deep the key is)

// and the cleaned line without any whitespaces

let (indentation, line) = cleaned_line_with_indentation(&line);

// Because our command_map can have multiple root keys

// we continue until we hit the `commands` key

if !is_parsing_commands {

if line == "commands" {

is_parsing_commands = true;

}

continue;

}

// How deep this key is

match indentation {

1 => { // one level in are locations

let location = line.to_string();

locations.push(location.clone());

current_location = Some(location);

}

2 => { // two levels deep are actions

// Parse the action if it's supported

if let Some(action) = CommandAction::from_command_parser(line) {

current_action = Some(action);

} else {

current_action = None;

continue;

}

}

3 => { // three are subjects

// Parse the subject

let subject = CommandSubject::from_command_parser(line);

let tuple = (current_location.clone(), current_action, subject);

// If we have all three we can construct a command

if let (Some(location), Some(action), Some(subject)) = tuple {

commands.push(Command { location, action, subject });

} else {

continue;

}

}

_ => { // something else is happening, this is no longer the commands part

is_parsing_commands = false;

continue;

}

};

}

Ok((CommandMap { commands }, locations))

}

// Calculates the indentation of a line

// either by counting tabs or two spaces as a tab

// and also cleanes the line so for example

// ` - switch:` becomes `switch`

fn cleaned_line_with_indentation(line: &str) -> (usize, &str) {

const START_WHITESPACES: &[char; 4] = &[' ', '\t', '-', '"'];

const END_WHITESPACES: &[char; 2] = &['"', ':'];

let mut spaces = 0;

let mut tabs = 0;

for c in line.chars() {

match c {

' ' => spaces += 1,

'\t' => tabs += 1,

_ => break

};

}

let space_indent = spaces / 2;

let tab_indent = tabs;

let cleaned = line

.trim_start_matches(START_WHITESPACES)

.trim_end_matches(END_WHITESPACES);

(space_indent + tab_indent, cleaned)

}

It’s a fair block of code but not that difficult to understand. We do need to add from_command_parser for CommandSubject and CommandAction. And additionally the is_same_action.

// command_action.rs

impl CommandAction {

pub fn from_command_parser(str: &str) -> Option<Self> {

match str {

// Default values are "zero" or off

"switch" => Some(Self::Switch(CommandSwitchValue::Off)),

"gradient" => Some(Self::Gradient(CommandGradientValue::Min)),

_ => None

}

}

// Just checks if the outermost enum is the same and doesn't care

// about inner values. On the command level a switch is a switch.

pub fn is_same_action(&self, other: &CommandAction) -> bool {

matches!((self, other),

(CommandAction::Switch(_), CommandAction::Switch(_)) |

(CommandAction::Gradient(_), CommandAction::Gradient(_)))

}

}

// command_subject.rs

impl CommandSubject {

pub fn from_command_parser(str: &str) -> Option<Self> {

Self::internal_from_str(str)

}

// Unified for several methods here

fn internal_from_str(str: &str) -> Option<Self> {

match str {

"light" => Some(Self::Light),

"teapot" => Some(Self::Teapot),

"windowblinds" => Some(Self::WindowBlinds),

"temperature" => Some(Self::Temperature),

"ventilator" => Some(Self::Ventilator),

_ => None

}

}

}

Phew. We’ve got our Commander ready now. But we’re just getting started. Didn’t we say we want to classify the commands? We’ll get into it now.

Classification

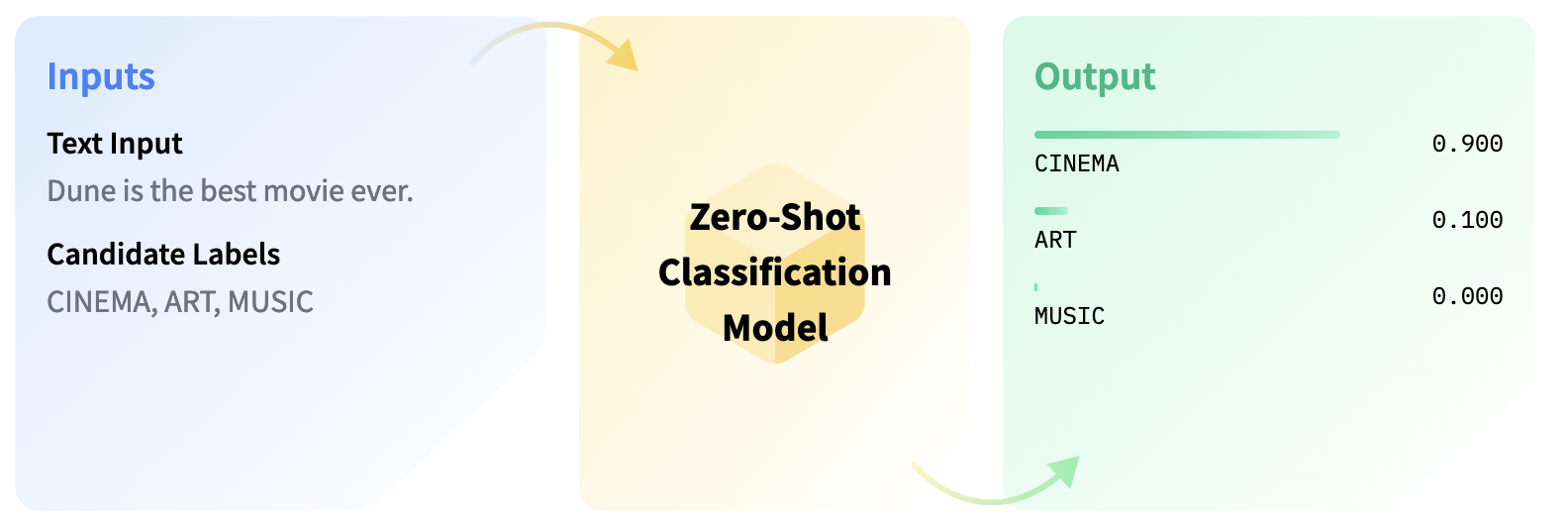

To get started with classification we need to solve the problem at a high level first. How to figure out that “Jarvis turn on the living room light” means that a command should be Switch(On) with Subject::Light and location: living room. There is a lot of potential approaches towards this problem with different AI models but I opted for using Zero Shot Classification which tries to assign labels to a piece of input data.

Zero shot classification

The above example illustrated how a zero shot classifier works. It takes a set of input labels and an input. It then assigns which label fits the input sentence best. This approach works well for our use case as well since we can easily generate labels from the command options and we can plug those in as the label set. And the actual input will the the STT sentence.

RustBERT

I’ve mentioned hugging face before and how they have a lot of models available to download there. For our uses we’ll use Goole’s BERT model that is very popular and is use prevalently in natural language processing. In particular we’ll use this Rust port. Installation of it is not the most straightforward on a M1 Mac like I was using though.

Installing RustBERT

The only way to get it working for me was installing a particular version of dependencies in order to get it working.

For pytorch or torchvision I used Homebrew and the version 0.17.0. Then for RustBERT my cargo dependencies are

rust-bert = { git = "https://github.com/guillaume-be/rust-bert", rev = "f99bf51f532d6d2ef5dfb05e21c536897888afd4" }

rust_tokenizers = "8.1.1"

tch = "0.15.0"

So a specific commit from git that uses tch 0.15 because the one on crates.io depends on 0.14 which is incompatible with other bits.

I recommend checking the Issues page on the repository as well.

Labeling commands

In order to label commands we’ll create a new trait called Labelable. Let’s add labelable.rs to traits.

pub trait Labelable {

// Create whatever implements this from a label

fn from_label(label: &str) -> Self;

// An array of labels for whatever implements this

fn labels() -> Vec<String>;

}

The trait allows us to equip various pieces of the command fields to be labelable. Let’s implement the trait now.

impl Labelable for CommandAction {

fn from_label(label: &str) -> Self {

match label {

"switch" | "turn off" => Self::Switch(CommandSwitchValue::Off),

"turn on" => Self::Switch(CommandSwitchValue::On),

"increase" => Self::Gradient(CommandGradientValue::More),

"decrease" => Self::Gradient(CommandGradientValue::Less),

"close" => Self::Gradient(CommandGradientValue::Min),

"open" => Self::Gradient(CommandGradientValue::Max),

_ => Self::Switch(CommandSwitchValue::Off)

}

}

fn labels() -> Vec<String> {

vec![

"turn on".to_string(),

"turn off".to_string(),

"increase".to_string(),

"decrease".to_string(),

"close".to_string(),

"open".to_string()

]

}

}

For a CommandAction we just have a way of getting an action from a label and vice versa.

impl Labelable for CommandSubject {

fn from_label(label: &str) -> Self {

match Self::internal_from_str(label) {

Some(subject) => subject,

None => Self::Light

}

}

fn labels() -> Vec<String> {

vec![

"light".to_string(),

"teapot".to_string(),

"windowblinds".to_string(),

"temperature".to_string(),

"ventilator".to_string()

]

}

}

Nothing too special here either. There is some fallbacks in case of a internal_from_str problem.

Classifier

That was a lot of supporting code but we have a solid foundation now that allows us to actually start using AI to figure out what command needs to be recognized.

Prerequisites

So now it’s time to start putting together our classifier. First let’s start with loading the model. We’ll put this functionality into processing/classifier.rs.

// Load the model

fn load_model() -> Result<ZeroShotClassificationModel, RustBertError> {

// Config allows us to tweak certain parameters

// and influence the classification process

// While I did play around with this the default

// configuration works well for the usecase

let config = ZeroShotClassificationConfig {

model_type: rust_bert::pipelines::common::ModelType::Bart,

..Default::default()

};

// Don't get mistaken. The actual weights are downloaded

// from the internet internally.

let model = ZeroShotClassificationModel::new(config)?;

Ok(model)

}

And we need a way to get the labels from previous steps.

// We keep them separate for a step later. And we'll cover intents in a bit

struct ClassificationLabels {

intents: Vec<String>,

locations: Vec<String>,

actions: Vec<String>,

subjects: Vec<String>

}

fn build_labels(commander: &Commander) -> ClassificationLabels {

ClassificationLabels {

intents: Intent::labels(),

locations: commander.locations.clone(),

actions: CommandAction::labels(),

subjects: CommandSubject::labels()

}

}

The code above shouldn’t look too surprising. The only thing is that we don’t append all of the labels together just yet. And now we’re ready to start classfication.

Failure reasons

Well almost. Because I’ll just include the full classifier.rs a bit further down we’ll go through the supporting structures first. One of these is a ClassificationFailureReason. If for example the user input is “Jarvis my knee hurts” it’ll be hard to construct a command from it. So we’ll define an enum to cover those cases.

// How sure we want to be to use a label

const SCORE_THRESHOLD: f64 = 0.85;

pub enum ClassificationFailureReason {

Unknown, UnsupportedInstruction, UnrecognizedInstruction

}

Intents

I wanted to decouple the user input part of commanding logic from the execution of command logic. That’s why before a final command (don’t confuse this with the Command struct) is executed it is transformed into an Intent. So in our jargon from now on we’ll use a Command for anything before classification and Intent for anything after classification. An intent can be or may fail to be executed. We’ll define an Intent struct now.

use crate::traits::labelable::Labelable;

use super::command::Command;

#[derive(Debug)]

pub enum Intent {

Command(Command),

Question(String)

}

impl Intent {

pub fn is_label_question(label: &str) -> bool {

label == "question"

}

}

impl Labelable for Intent {

fn from_label(label: &str) -> Self {

unimplemented!("{}", label);

}

fn labels() -> Vec<String> {

vec!["command".to_string(), "question".to_string()]

}

}

So we have two things that can be executed. A command or Jarvis can answer questions! Didn’t I say I might add some nuggets here and there. Well the quality of answers is still to be seen. And we’ve added the Labelable implementation and a shorthand check because we don’t want to expose concrete label values to the outside. You can see that from_label is unimplemented! because there’s really no way to construct a fully fledged Command from a label command. But it helps us recognize what the user is requesting of Jarvis.

Constructing intents

The output of our classification will be an array of Label objects. This is an internal RustBERT struct but what’s important for us is: it has a text property and a score property. The text is the value we pass and the score is how sure the model on the correlation of this label to the input text. We’ll implement a helper function to construct an intent from the model output.

// We pass the original instruction of the user eg "Jarvis turn on the light"

// and an array of labels, and our ClassificationLabels

// And we return an tuple consisting of an Intent and the overall

// score on how sure we are about this classification

fn intent_from_classification(instruction: &str, model_output: &Vec<Label>, data: &ClassificationLabels) -> (Intent, f64) {

// Tuples for storing the action location and subject

// first field is the score they were given and second is their

// index in the `model_output`

let mut action: (f64, usize) = (0.0, 0);

let mut location: (f64, usize) = (0.0, 0);

let mut subject: (f64, usize) = (0.0, 0);

// Loop through the labels

for (i, label) in model_output.iter().enumerate() {

let score = label.score; // Pull out the score

// Figuring out if it's a question is a bit special

// If this is an intent label and we're sure of what it is

if data.intents.contains(&label.text) && score > SCORE_THRESHOLD {

// Only in the case of a recognized question we return early

if Intent::is_label_question(&label.text) {

// And pass along the actual user input

return (Intent::Question(instruction.to_string()), score);

}

// Otherwise figure out which category of labels this belongs to

} else if data.actions.contains(&label.text) && score > action.0 {

action = (score, i);

} else if data.subjects.contains(&label.text) && score > subject.0 {

subject = (score, i);

} else if score > location.0 { // it's a location

location = (score, i);

}

}

// Determine the minimum score of all the selected labels

let score = action.0.min(location.0).min(subject.0);

// Construct a command

let command = Command {

location: model_output[location.1].text.clone(),

action: model_output[action.1].text.parse::<CommandAction>().unwrap(), // One of the few scenarios where I'm okay with an unwrap

subject: model_output[subject.1].text.parse::<CommandSubject>().unwrap()

};

let intent = Intent::Command(command);

// Finally return the intent

(intent, score)

}

The function above figures out if the given instruction was a command or a question. If it’s a question it’s returned as an intent to be handled further down the pipeline. If it’s a command it’s assembled so that it is fully formed. However we’re missing some implementaion on various command fields to support text.parse::<CommandSubject>(). To add that we need to implement the FromStr trait.

// command_action.rs

impl FromStr for CommandAction {

type Err = ();

fn from_str(s: &str) -> Result<Self, Self::Err> {

Ok(Self::from_label(s))

}

}

// command_subject

impl FromStr for CommandSubject {

type Err = ();

fn from_str(s: &str) -> Result<Self, Self::Err> {

Ok(Self::from_label(s))

}

}

We reuse the functionality we’ve already added! Goodie.

main

That was already a lot of the heavy lifting taken care of. What’s left now is to tie the various pieces together to complete recognizer.rs. I’ll add the full code for it below. Most of it should already look familiar. The only thing left to cover is the actual main function.

use std::sync::mpsc::{Receiver, Sender};

use rust_bert::{pipelines::{sequence_classification::Label, zero_shot_classification::{ZeroShotClassificationConfig, ZeroShotClassificationModel}}, RustBertError};

use crate::{core::commander::Commander, model::{command::{self, Command}, command_action::CommandAction, command_subject::CommandSubject, intent::Intent}, traits::labelable::Labelable};

// A typealias so that we don't have to type the long variant

pub type ClassifierOutput = Result<Intent, ClassificationFailureReason>;

const SCORE_THRESHOLD: f64 = 0.85;

struct ClassificationLabels {

intents: Vec<String>,

locations: Vec<String>,

actions: Vec<String>,

subjects: Vec<String>

}

pub enum ClassificationFailureReason {

Unknown, UnsupportedInstruction, UnrecognizedInstruction

}

pub fn main(command_rx: Receiver<String>, intent_tx: Sender<ClassifierOutput>) -> Result<()> {

let model = load_model()?; // Load the model

let commander = Commander::new(); // Create the commander and parse

let labels = build_labels(&commander); // Build labels

// Here we chain them into a single array

let model_labels: Vec<&str> = labels.locations

.iter()

.chain(labels.actions.iter())

.chain(labels.subjects.iter())

.map(|s| s.as_str())

.collect();

while let Ok(instruction) = command_rx.recv() {

// We could classify multiple input strings but we only

// need one so we create a vec here

let inputs = vec![instruction.as_str()];

// We do a multilabel prediction since we want multiple labels

// assigned not the most likely one

let output = match model.predict_multilabel(inputs, &model_labels, None, 128) {

Ok(result) => result,

Err(_) => { // If it failed we let the pipeline know

if intent_tx.send(Err(ClassificationFailureReason::Unknown)).is_err() {

break;

}

continue;

}

};

// Generate the intent

let (intent, score) = intent_from_classification(&instruction, &output[0], &labels);

let result: Result<Intent, ClassificationFailureReason>;

// Check if the score isn't high enough to be treated

// as a success

if score < SCORE_THRESHOLD {

println!("Instruction unclear: '{}'\nScore {} with output: {:?}\n", instruction, score, output[0]);

result = Err(ClassificationFailureReason::UnrecognizedInstruction);

} else if let Intent::Command(ref command) = intent {

// Check if the command is supported

if commander.supports_command(command) {

result = Ok(intent);

} else {

// If not we created a combination that isn't supported

result = Err(ClassificationFailureReason::UnsupportedInstruction);

}

} else if let Intent::Question(_) = intent {

result = Ok(intent);

} else { // Shouldn't really happen

println!("No suitable command for '{}'\n", instruction);

result = Err(ClassificationFailureReason::UnsupportedInstruction);

}

if intent_tx.send(result).is_err() {

break;

}

}

Ok(())

}

fn load_model() -> Result<ZeroShotClassificationModel, RustBertError> {

let config = ZeroShotClassificationConfig {

model_type: rust_bert::pipelines::common::ModelType::Bart,

..Default::default()

};

let model = ZeroShotClassificationModel::new(config)?;

Ok(model)

}

fn build_labels(commander: &Commander) -> ClassificationLabels {

ClassificationLabels {

intents: Intent::labels(),

locations: commander.locations.clone(),

actions: CommandAction::labels(),

subjects: CommandSubject::labels()

}

}

fn intent_from_classification(instruction: &str, model_output: &Vec<Label>, data: &ClassificationLabels) -> (Intent, f64) {

let mut action: (f64, usize) = (0.0, 0);

let mut location: (f64, usize) = (0.0, 0);

let mut subject: (f64, usize) = (0.0, 0);

for (i, label) in model_output.iter().enumerate() {

let score = label.score;

// Figuring out if it's a question is a bit special

if data.intents.contains(&label.text) && score > SCORE_THRESHOLD {

// Only in the case of a recognized question we return early

if Intent::is_label_question(&label.text) {

return (Intent::Question(instruction.to_string()), score);

}

} else if data.actions.contains(&label.text) && score > action.0 {

action = (score, i);

} else if data.subjects.contains(&label.text) && score > subject.0 {

subject = (score, i);

} else if score > location.0 { // it's a location

location = (score, i);

}

}

let score = action.0.min(location.0).min(subject.0);

let command = Command {

location: model_output[location.1].text.clone(),

action: model_output[action.1].text.parse::<CommandAction>().unwrap(),

subject: model_output[subject.1].text.parse::<CommandSubject>().unwrap()

};

let intent = Intent::Command(command);

(intent, score)

}

Didn’t I say this was going to be a long post? But we’re nearly there! This is now the entire coassifier.rs. The only function worth a mention is predict_multilabel. The input is:

- The instruction converted into a proper format

- The possible labels we want to use for classification

- The template for fine tuning the labeling process. We use

None - Max size of the input limited to 128 characters.

The output of it was covered before in the intent_from_classification. We only make sure an error didn’t occur and if it did we’d like the user to know about it at this point.

Integrating with main

One last thing left to do is to integrate the classifier back into our main.rs.

let (classifier_tx, classifier_rx) = channel::<ClassifierOutput>();

let classifier_signals = signals.clone();

thread_pool.spawn_blocking(move || {

processing::classifier::main(recognizer_rx, classifier_tx)

.map_err(|e| classifier_signals.set_shutdown(Some(e)))

.ok();

println!("Classifier shutting down");

});

If you’re still reading congratulations! I know this was a lot but we’ve actually implemented the brain of Jarvis! It gets easier from now on. Or does it? We’ll see in the next post